What Can College Students Expect in 2023-24?

Around two million new freshmen enrolled in college as part of the rising class of 2027. Those students’ high school careers were thrown into disarray by the COVID pandemic. But, as higher education settles into its post-pandemic reality, what can those students expect to face—and how can private-sector scholarships help as they work toward their associate’s, bachelor’s and graduate degrees?

Filed In

- Supporting Students

Topics

- College Costs

Around two million new freshmen enrolled in college as part of the rising class of 2027. Those students’ high school careers were thrown into disarray by the COVID pandemic. But, as higher education settles into its post-pandemic reality, what can those students expect to face—and how can private-sector scholarships help as they work toward their associate’s, bachelor’s and graduate degrees?

Costs will keep rising.

It’s not news to anyone that college keeps getting more expensive. As Forbes reports, “Between 1980 and 2020, the average price of tuition, fees, and room and board for an undergraduate degree increased 169%,” thanks to a well-documented confluence of factors. Sharp cuts in state and federal funding, especially after the 2008 recession, led to a need to bring in more tuition revenue, and competition for enrollment has led schools to spend more on administration, services and amenities.

The good news is that some states are beginning to reinvest in higher education. According to the same Forbes piece, “As of 2020, average public higher education funding increased for eight years in a row, according to [a] report from the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association (SHEEO), and 18 states have brought funding up to pre-2008 levels.”

But it hasn’t stopped costs rising on a national scale. “[I]n 2020, average education appropriations per full-time equivalent student were still 6% lower overall than in 2008, according to [the] report.” What does that mean for the class of 2027? Public four-year in-state costs rising from $23,000/year to $26,000/year (or private four-year costs rising from $55,000 to $60,000/year) over the course of their bachelor’s program.

The investment is worth it—if students graduate.

With the ever-rising cost of college, plenty of recent high school graduates are wondering whether it’s all worth it. The Seattle Times reports “The proportion [of graduates] who enroll in the fall after they finish high school is down from a high of 70% in 2016 to 63% in 2020, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.” And while the pandemic exacerbated that dip in enrollment, the decrease has continued even after returning to “normal.”

However, in spite of skepticism that’s growing along with tuition bills, the numbers are still clear: attending and completing college is a solid investment. As reported by Third Way, “The typical college graduate will earn roughly $900,000 more than the typical high school graduate over their working life. … Even after controlling for potential biases and risks, it’s still worth it. The net present value of a college degree is $344,000 for the average person.”

The caveat to that value, of course, is that students who start college, accrue debt, and leave before graduating can end up worse off than if they’d never gone at all. The Third Way piece goes on to quantify: “While the students with six-figure levels of debt are often the focus of stories in the popular press, they are the exception rather than the rule. These students make up only 5%of the population that takes out student loans, and many of them are in high-return graduate programs like medical school or law school. Arguably the much bigger problem are students who take out some—often smaller amounts— of debt, but never graduate.”

Racially and economically marginalized students have the most ground to make up.

Unfortunately, the students most likely to find themselves in that situation are those from low-income, high-poverty and historically marginalized communities. According to the 2022 NSC Benchmarks study:

Persistence rates were higher for higher-income high school graduates than their low-income high school counterparts (86% vs 76%) … Completion rates were much higher for students from higher-income schools versus low-income schools (52% vs 30%). Similarly, completion rates were higher for students from low-poverty schools versus high-poverty schools (61% vs. 25%).

In short, if you graduated from a school in an affluent community in 2023, you’re much more likely to be a debt-free member of the college class of 2027.

That’s especially true for those who go directly to four-year schools rather than starting at community colleges—and that means an uphill road for Black and Hispanic students, and an even steeper hill for women of color. As reported by the Seattle Times:

While four out of five students who begin at a community college say they plan to go on to get a bachelor’s degree, only about one in six of them actually manages to do it. That’s down by nearly 15% since 2020, according to the clearinghouse.

These frustrated wanderers include a disproportionate share of Black and Hispanic students. Half of all Hispanic and 40% of all Black students in higher education are enrolled at community colleges, the American Association of Community Colleges says.

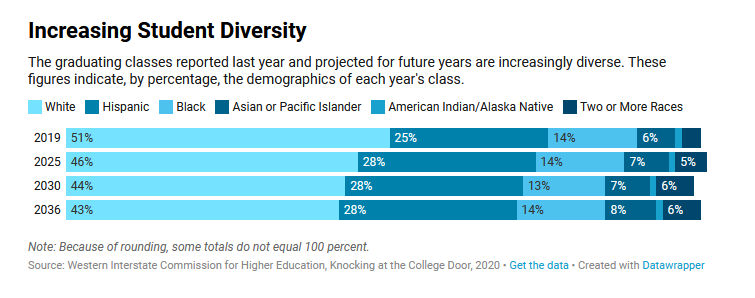

As future graduating classes become more and more diverse, this gap threatens to widen.

As Demaree Michelau, president of the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education (which produced the chart above), told the Chronicle of Higher Ed, “These data just put the exclamation point on what we need to do as an education system, from beginning to end. That includes better serving all of our students, in particular students of color, low-income students, and first-generation students.”

Private-sector scholarships can, should and will play a major role in that service. Research done by Scholarship America in conjunction with MIT’s Blueprint Labs shows that first-generation, BIPOC and Pell Grant-eligible students who receive private scholarships see their chances of graduation grow by 10-12%—the biggest boost for any population. That’s why we’re working with our partners to designate more scholarship dollars to the people who need them most: our goal, by the time the Class of 2027 graduates from college, is to award at least half of our scholarship dollars to students from historically marginalized populations who are facing financial need.

By making a conscious, data-driven effort to support these students in need, we can truly move the needle on college graduation rates. And that’s why supporting and partnering with Scholarship America can ensure you’re making the biggest impact possible as the high school Class of 2023 works to become the college Class of 2027.

Related Articles

Browse All

Equitable Foundation + Syracuse College Attainment Network: Supporting Students Together

Scholarship America Program Q&A: Chevron Phillips Chemical Dependent Scholarship Program

Our team is here to help you achieve your goals and build your custom scholarship program.