Understanding College Financial Aid eBook

Financial aid for college is confusing. We’re here to help. Read this eBook for a comprehensive look at financial aid including the FAFSA, Financial Aid Offers and scholarships.

Filed In

- Paying for College

- Resources

Topics

- FAFSA

- Financial Aid

- How to Pay for College

- Scholarships

The Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA)

For students looking for financial support to attend school, filling out the Free Application for Federal Student Aid—the FAFSA—is the first place to start.

Like the name says, the FAFSA is entirely free, and it determines what kind of aid you may be able to get from the federal government. But it does much more than that: states use your FAFSA data to determine if you’re eligible for statewide aid, and almost every college looks at your FAFSA to figure out their financial aid offers to you as well. It’s the single most important piece of the process. Here are the five things you need to know before you start.

1. When can I start my FAFSA?

The FAFSA is available to students every year starting October 1, and you should try and get as early a start as possible. Thanks to recent simplifications, the FAFSA now connects directly to the IRS, and can pull in your family’s tax data from the previous year.

2. What is the deadline for submitting my FAFSA?

Remember, you need to fill out the FAFSA every year, not just your senior year of high school.

The Federal FAFSA deadlines are a little deceiving. While you can technically fill out the application anytime between October 1 and June 30, waiting that long would be a big mistake. Most states and schools have earlier deadlines, with February and March typically being important months in a lot of places. In lots of cases, state and school funds are first-come, first-served, so it’s always in your best interest to fill out your FAFSA as soon after October 1 as you can.

Check the list of state deadlines for the FAFSA on the Federal Student Aid government website. When it comes to your school’s specific deadlines, add a calendar reminder in mid-August to double-check about deadlines, and find out if you can take advantage of any early FAFSA opportunities. While many institutions will still accept your FAFSA submission past their initial deadline, applications submitted before then take precedence and will receive earlier award letters.

Remember, you need to fill out the FAFSA every year, not just your senior year of high school.

Finally, the number one mistake with the FAFSA is not filling it out, so regardless of where you are in the process it’s always worth it to complete.

3. Am I a dependent or not?

Many students get tripped up on whether they classify as an independent or dependent. This can get especially tricky for upperclassmen who may not live with their parents or legal guardians, but still qualify as a dependent. Remember: just because parents opt not to help pay for school does not grant someone independent status. Download this questionnaire from the FAFSA website to determine your dependency status.

While this may seem like a small question, your dependency status actually determines whose tax information needs to be provided. Dependent students who fail to provide their parent information risk having their forms rejected. This means no Expected Family Contribution (EFC) will be calculated—and most schools require an EFC in order to issue award letters, including merit-based scholarships (more on EFCs later). Miss this step, and you may severely restrict your options.

4. Who are my parents, anyway?

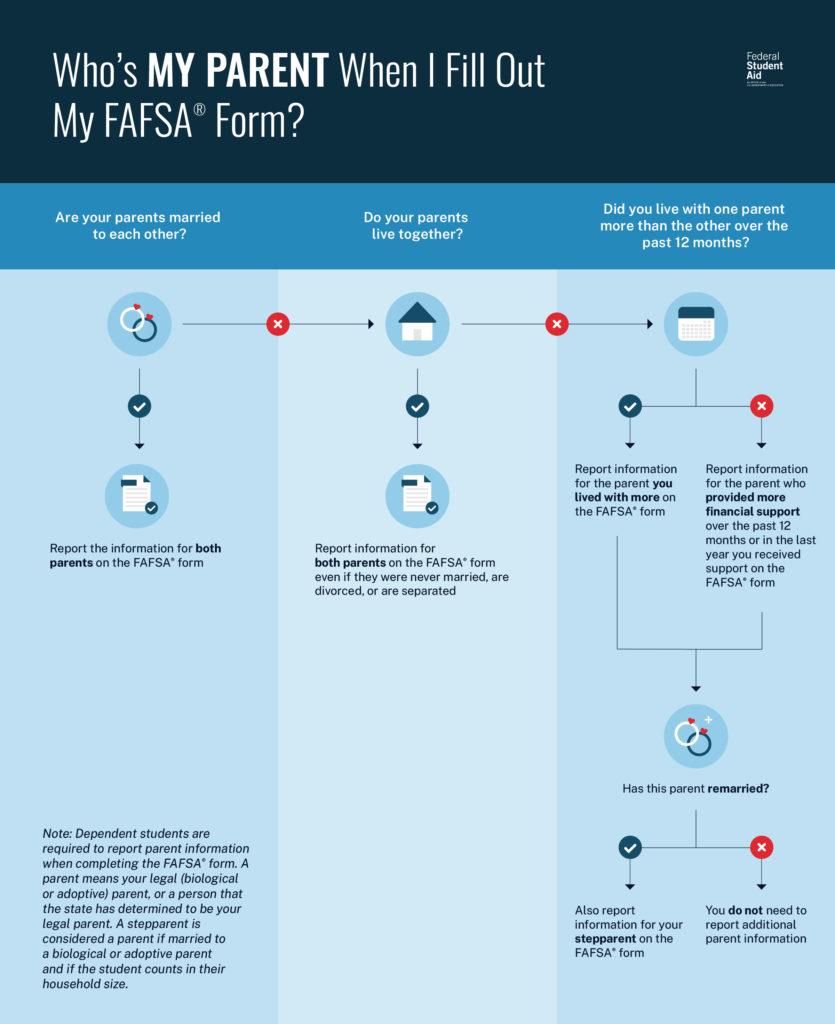

This may seem like a crazy question, but it’s actually the part of the FAFSA that gets the most confusing. Students whose parents have separated or who have been placed in legal custody of another relative may wonder whose information they need to include. This is important to determine, as it affects whose information is included in the parent tax records that calculate the EFC.

Read the legal definitions of terms carefully as they will help clarify who should provide information. It is not as simple as just including the information of the people you live with. If you live in the custody of another person, you cannot use their information unless they have legally adopted you. To help you determine whose information should be included in the parent section of your FAFSA, check out this handy flowchart:

If you do not know your parents or your parents refuse to provide their information, the FAFSA website has a more information regarding your options.

5. What is work-study?

Work-study is a special type of part-time job provided by your college where you can earn money toward your education expenses. When filling out the FAFSA, you can indicate whether you’re interested in a work-study job. A lot of first-time FAFSA filers assume that indicating interest in work-study means you must take a work-study job. That’s not true – and misreading can mean missing out.

If you are awarded potential work-study dollars, you can choose whether or not to commit to a work-study program. However, if your FAFSA says you are not interested in work-study, you will not be eligible for any work-study programs or dollars whatsoever during that year. Unless you’re certain of your work situation, don’t miss out on potentially valuable dollars and opportunities by saying “no” on the FAFSA.

Need more help with your FAFSA? The Form Your Future initiative, created by the National College Access Network, has a ton of helpful resources and experts to answer your FAFSA questions. Visit formyourfuture.org to learn more.

Student Aid Report and Financial Aid Offer

Once you’ve submitted your FAFSA, you’re going to be waiting for two very important documents. The federal government will send you one, called a Student Aid Report (SAR). The other, called a Financial Aid Letter (or Financial Aid Offer), will come from your current or future college. Here’s what to know about those two documents.

What to expect from your Student Aid Report (SAR)

The Student Aid Report (SAR) is delivered electronically to the email address used on your FAFSA, and it can take anywhere from three days to a couple of weeks, depending on system traffic. We recommend adding “ed.gov” to your email safe sender list so you don’t miss out on your SAR—and keep an eye on your junk mail and spam folders just in case. Once the SAR arrives, carve out some time (with your family, if possible) to go over it carefully. Mistakes on your FAFSA aren’t the end of the world and can be corrected online by students or their schools—but if you don’t catch them right away, the process is a lot more complicated. (If you want to give a college access to change FAFSA information, look for the Data Release Number, a four-digit reference number found below the Expected Family Contribution box.)

The SAR’s most important number is the Expected Family Contribution (EFC): the amount of money that your family is expected to contribute to your education.

The SAR’s most important bottom-line number is the Expected Family Contribution (EFC): the amount of money that your family is expected to contribute to your education. This is the number that statewide and college financial aid offices will use to calculate how much financial aid they’ll give you. The lower the EFC, the more financial aid you’re likely to qualify for.

If that EFC number seems higher than you thought, here’s a good explanation from FinAid:

“You may find your EFC figure to be painfully high. This often occurs because the need analysis formulas are heavily weighted toward current income. In addition, the formulas consider your income and assets without taking many common forms of consumer debt into account, such as credit card balances and auto loans. Finally, student income and assets can add significantly to the EFC figure.”

FinAid does list some strategies for reducing your EFC and maximizing financial aid eligibility at this stage, but keep in mind that these may take months or years of long-term planning to put into effect. For most families, it’s best to work with the EFC you receive, and figure out how to maximize aid from your college. That’s where the Financial Aid Letter comes in.

Making sense of financial aid letters and “unmet need”

The financial aid letter is a document that comes from your college or university that outlines the cost to attend, as well as the federal, state and school-funded awards you’re eligible to receive to help pay for it. The dollar amount offered in a financial aid letter makes it a powerful piece of correspondence that has the potential to make or break enrollment decisions.

Although financial aid letters vary from school to school, there’s one important phrase that your family should consistently be thinking about related to them, and that’s unmet need. Unmet need is the amount that’s left to be paid after financial aid is awarded. It’s the amount that the college says you and your family can actually afford to pay. Here’s a helpful sample financial aid letter (view the full interactive tool here):

In this example, you’ll need to do some digging to find the unmet need. The Cost of Attendance (COA) is $38,250, and the Expected Family Contribution (EFC) is $4,500. The EFC can be combined with grants and scholarships as well as Federal Work-Study to get a total of $19,926 in financial aid.

Pay close attention to the details of the line items as the total aware amount can be misleading. The bottom of the letter makes it seem like the awards total $38,250: enough to cover full tuition with no unmet need. However, loans that need to be paid back are included within the line items.

Upon closer look, the letter contains $19,926 in grants and scholarships, which don’t need to be repaid. However, the last five lines are all different types of student loans, which do—potentially leaving you with considerable debt after graduation. The awards list doesn’t separate these options, so it would’ve been up to you and your family to figure out if you really want to rely on loans to cover the $13,824 in unmet need.

Most schools don’t have the funds to cover the financial needs of every student enrolled. Rather than being surprised by the unmet need, use the number as motivation to find “free money.”

This is just one way in which financial aid letters can be confusing. They vary by school, they can be hard to interpret and can be overwhelming. To ensure you’re not missing anything major, sit down with your family or a mentor to compare financial aid letters from your potential schools, and to see what your unmet need really is at each institution. Researching and discussing both your financial aid letter and your scholarship options will reduce stress and ensure you’re prepared for fluctuations in future years.

Most schools don’t have the funds to cover the financial needs of every student enrolled. Rather than being surprised by the unmet need, use the number as motivation to find “free money.” You’ll notice on the sample letter that private scholarships—those from businesses, competitions and organizations like Scholarship America—aren’t listed, and those can go a long way toward reducing unmet need.

Scholarships

Scholarship America believes in the vital importance of scholarships as part of your financial aid package. Students from all walks of life and with all kinds of skills can earn scholarships, and they can go a long way toward making financial aid less stressful. But even the free money that comes from scholarships can have some unintended consequences. Here’s how to make sure you’re getting the most out of your hard-earned awards!

Financial Aid Displacement

This might surprise you, but not all colleges treat your scholarship dollars the same way. Some colleges will reduce the amount of need-based grant aid, loans, and/or work-study if you get a scholarship. Think this is unfair? Us too. But it’s a fact of life for some students.

After you submit your FAFSA, colleges will send you a Financial Aid Letter (or Financial Aid Offer) and determine your “unmet need”, which is money that you and your family have to cover in addition to your Expected Family Contribution (EFC). Scholarships can help reduce unmet need or eliminate it all together depending on the total amount you receive—but only if your college of choice will apply the money that way.

Unfortunately, some schools use “financial aid displacement,” a practice in which students’ financial aid awards are reduced when they add private scholarships to their family contribution. Follow these three tips to ensure your scholarships receive fair treatment.

1. Research the college’s outside scholarship policy

“Outside” scholarships, also called “external” or “private” scholarships, are those scholarships you receive from sources other than the college. Your outside scholarship may include community-based scholarships (like Dollars for Scholars, a program of Scholarship America, or those from the Rotary, Elks, your high school foundation, or your church); scholarships from your parents’ employers; or scholarships you earn as a result of a larger regional or national competition.

Look for schools that apply scholarships to the unmet need portion of your financial package, rather than those that will reduce the amount of institutional grant aid.

Some colleges share their policy toward outside scholarships right on their websites. Make sure you search the college websites for both “outside scholarship policy” and “external scholarship policy,” as they may go by either name. For those colleges that don’t list their policy, you will need to ask your college financial aid officer. Look for schools that apply scholarships to the unmet need portion of your financial package, rather than those that will reduce the amount of institutional grant aid.

2. Talk with your financial aid officer

See if your college financial aid officer will first apply your outside scholarship(s) to your unmet need, and if there are dollars remaining, use the scholarships to reduce your loans. Some schools may also adjust the cost of attendance to include the cost of a computer, art supplies, or other expensive gear to help you keep the full amount of your outside scholarship. It’s always worth it to ask.

3. Ask your scholarship sponsor to defer all or part of your scholarship

If you’ve hustled to find every scholarship you can, there’s a possibility that you’ll end up with an “overaward”—more financial aid than you need to cover your tuition and fees for the year. It’s uncommon, but it can result in losing the “extra” part of your funds. In this case, you should reach out to the organization that provided the scholarship and request to defer all or part of it to a future academic year. (Typically, overawards happen to freshmen who earned a lot of scholarships in high school. If this is you, you’ll be happy to have the extra money coming in your sophomore year!)

All of this might have you considering keeping your scholarships a secret from your college, but that could be even more costly. Federal law requires students to disclose all scholarships when federal financial aid plays a role in your aid package. If you don’t report your outside scholarships, you may be required to repay the school or the federal government all or part of your need-based financial aid package.

Scholarships as taxable income

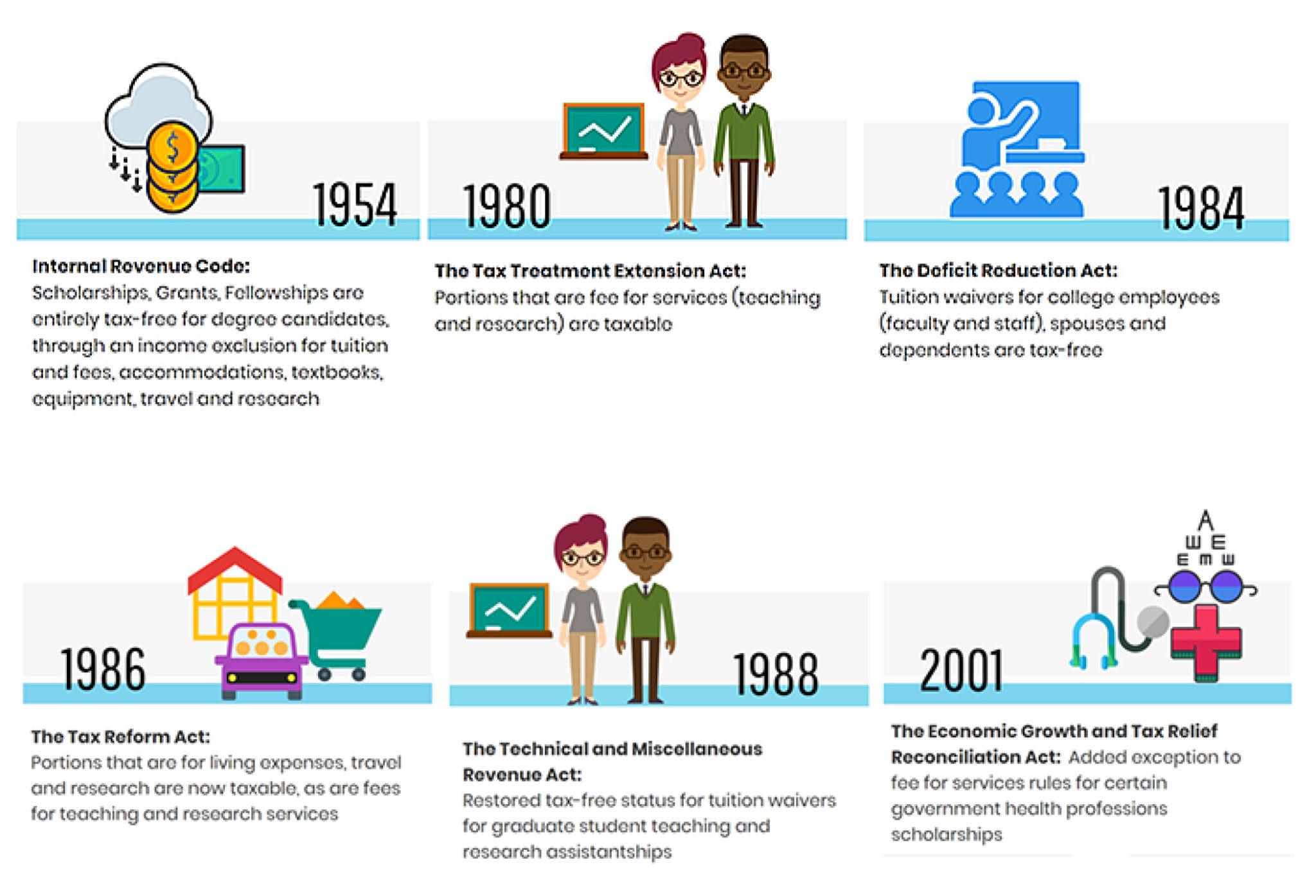

Displacement isn’t the only way you can lose a portion of your scholarship. While it’s not common, there are a few situations in which scholarship funds may be treated as taxable income.

Until 1980, all scholarships, grants and fellowships were tax-free, no matter what they were used for. However, changes in laws since then have divided scholarship funds into two broad categories. Those that are used on costs such as tuition, fees, books and supplies are tax-free. But scholarships and grants that apply toward other mandatory college living expenses including housing, food, transportation, and childcare, are taxable.

But wait, aren’t living expenses a big part of college expenses?

Yes, as we know, housing expenses alone are a large and growing part of the cost to attend college. According to The College Board, 2017-18 undergraduate living expenses make up over half of all college expenses. And for students attending 2-year colleges, living expenses make up more than 70 percent of the cost to attend. This means even if you’re attending college “for free,” you might owe more than you think.

Will I be taxed on my scholarships and grants?

Every case is different, but here are some of the most likely students to face taxes on their scholarship aid.

- Students who receive a “full-ride” scholarship could have a tax liability because the portion of the scholarship used for college living expenses is currently taxable.

- Students who work throughout the year will probably earn enough to surpass the tax filing threshold. The average annual work earnings of an enrolled undergraduate student working a 29-hour work week were $16,000 – this is well above the income threshold above which a tax return must be filed.

- Students who receive emergency financial aid or other mixed federal, state or institutional grants could also be impacted and pay tax on the portions of those funds used for college living expenses.

- Graduate students, who often work more, or students pursuing fellowships or professional degrees could face tax liability on their scholarships and paid fellowships.

Scholarship America and other organizations are working hard to limit the tax burden on scholarship recipients. However, for now, it’s important to know that some of your scholarship or grant funds may be taxable. Your financial aid advisors want you to make the most of your awards—if you’re running into any of the situations above, we recommend working with them to figure out the best way to reduce your tax liability and make the most of your scholarship!